Don’t want to read? Listen to the podcast.

Consumer product regulation in the United States has evolved over more than a century, driven by public health crises, environmental disasters, social activism, and economic change. What began as a reaction to dangerous patent medicines and food adulteration in the early 1900s has grown into a complex framework of federal and state agencies overseeing everything from formulated household goods to high-tech electronics. Compliance professionals today must navigate laws and standards enforced by multiple regulators – from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), the Department of Transportation (DOT), and state agencies – each with their own historical mandate. This post provides a chronological narrative of how U.S. consumer product regulations came to be, highlighting pivotal moments (like the creation of the FDA, EPA, CPSC, and DOT hazardous materials rules) and major laws (such as the Federal Hazardous Substances Act, Toxic Substances Control Act, and Resource Conservation and Recovery Act). We’ll explore why government enforcement expanded across manufacturers, suppliers, and retailers – and how social, environmental, and economic forces shaped these changes – from early industrialization through the modern e-commerce era.

Figure: A 19th-century patent medicine, “Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup,” was marketed for teething infants – but secretly contained morphine. Such quack remedies caused poisonings and deaths, fueling public outrage and demands for government action (DEA Museum).

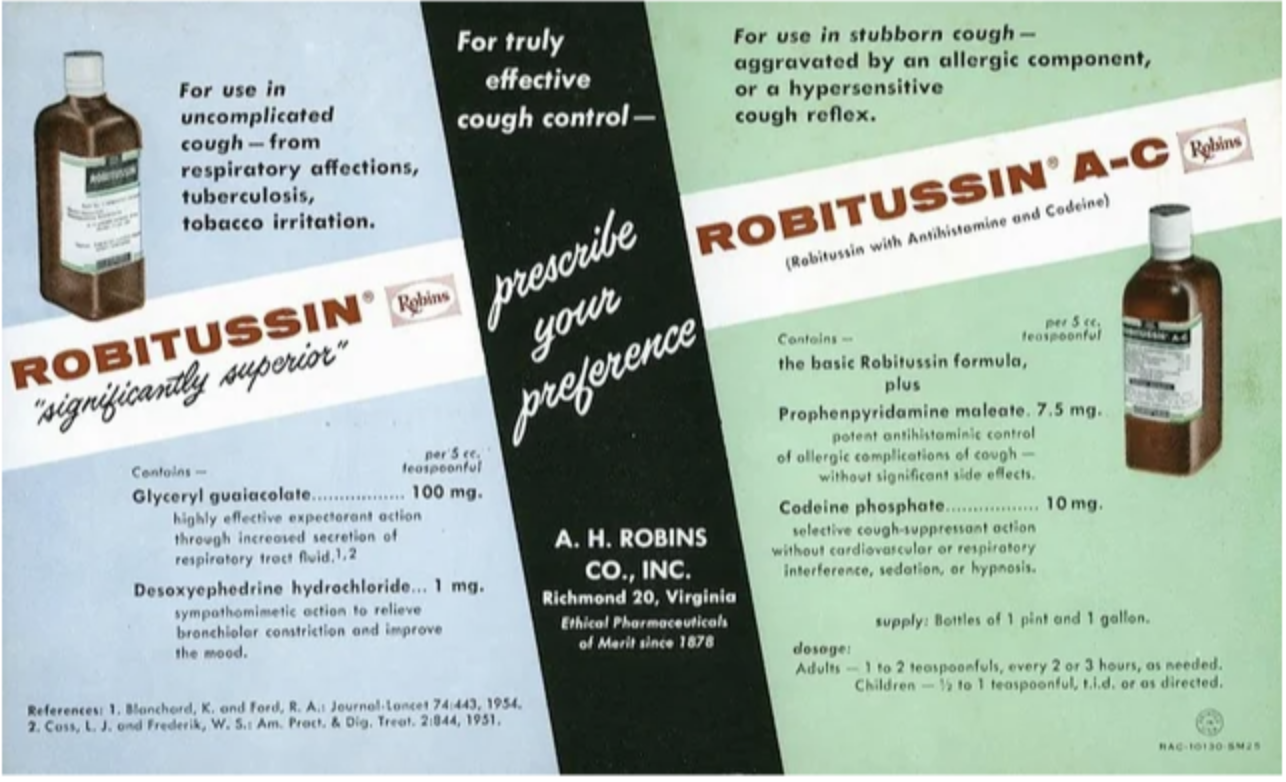

By the turn of the 20th century, the rapid growth of industrial manufacturing had led to widespread food and drug safety problems. Medicines and food products were often unregulated, resulting in dangerous concoctions and adulterated foods being sold to an unaware public. The tipping point came with “patent medicines” – over-the-counter remedies like Mrs. Winslow’s Syrup – which contained narcotics or toxins that sometimes proved fatal to children.

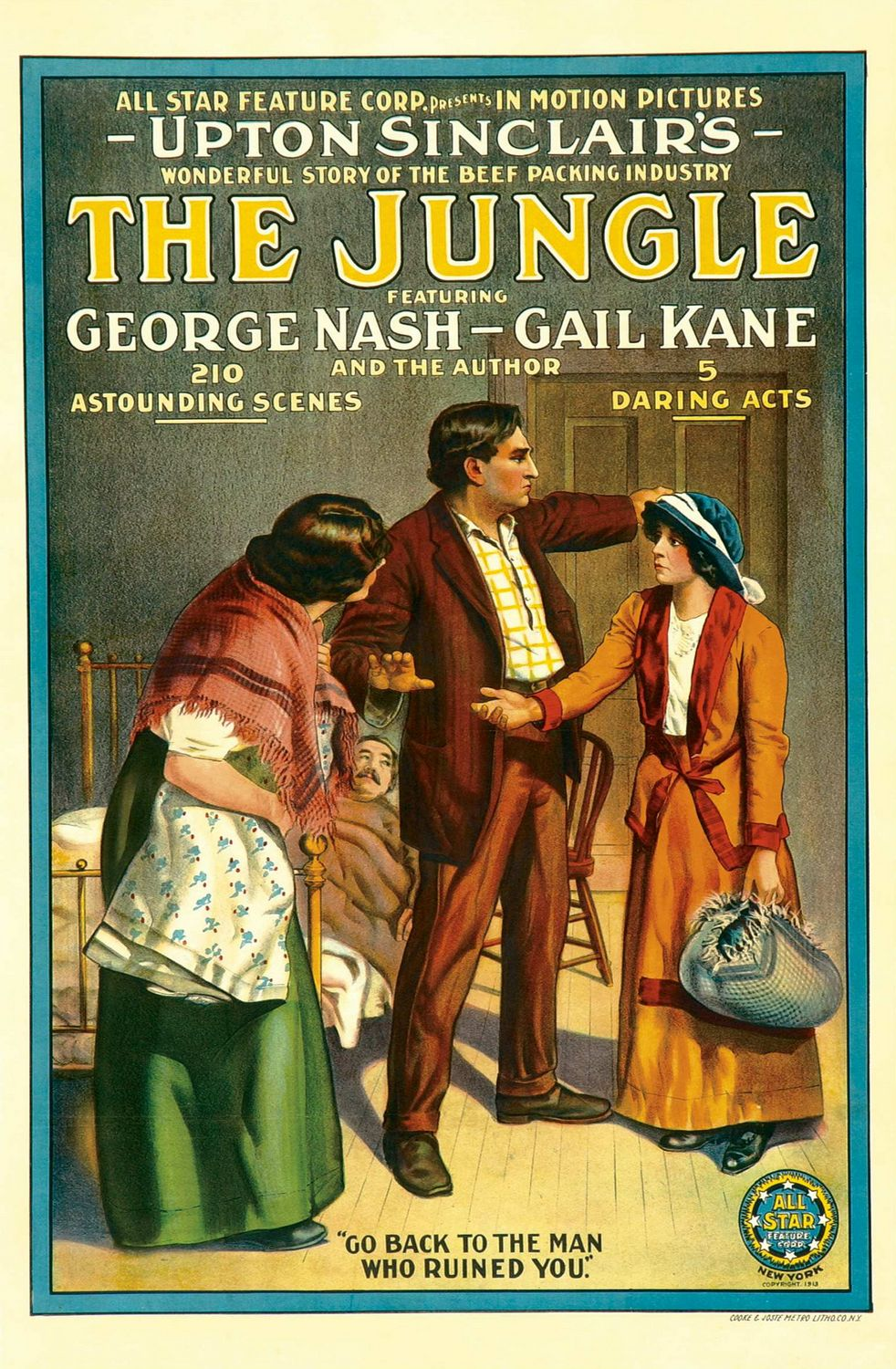

At the same time, meat packing plants were exposed for filthy conditions, and producers commonly used poisonous preservatives and dyes in foods. These shocking disclosures of unsanitary and deceptive practices ignited public outrage, leading President Theodore Roosevelt and Congress to act. In 1906, the Pure Food and Drugs Act was signed into law, launching the first federal oversight of consumer products. This landmark law (enforced by the Bureau of Chemistry, predecessor to the FDA) prohibited interstate commerce in misbranded or adulterated foods, drinks, and drugs. On the same day, Congress also passed the Meat Inspection Act to clean up the meat industry. The driving force behind these laws was clear – public health crises and muckraking journalism (like Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle) had exposed that lack of regulation was literally killing people. As the FDA later recounted, “shocking disclosures of insanitary conditions in meat-packing plants, the use of poisonous preservatives and dyes in foods, and cure-all claims for worthless and dangerous patent medicines were the major problems leading to the enactment of these laws.”

The new 1906 law gave federal authorities the power to seize unsafe products and punish violators, but it had limitations. For example, it did not require proof of a drug’s effectiveness, and false therapeutic claims were not explicitly outlawed (a loophole closed by the Sherley Amendment in 1912). Over the next few decades, the FDA (officially named in 1930) struggled to keep up with a marketplace of ever-more complex consumer goods with its relatively narrow authority. Tragedy again spurred change: in 1937, over 100 Americans (many children) died from a toxic drug solvent in “Elixir Sulfanilamide,” a scandal that dramatized the need for stronger pre-market controls on product safety. The following year, Congress enacted the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938, overhauling the 1906 law. This expanded the FDA’s reach to cosmetics and medical devices, required that new drugs be proven safe before marketing, and added enforcement tools like factory inspections and court injunctions. It also demanded truthful labeling (with certain ingredients like narcotics plainly listed) and empowered the FDA to set tolerance limits for poisonous substances in foods. For the first time, regulators could act before people were harmed, not just react after the fact – a pivotal shift in enforcement philosophy.

The post-World War II era brought an explosion of new consumer products and synthetic chemicals into American homes. Prosperity and technological advances meant more packaged foods, plastics, medicines, and appliances – but also new risks. By the late 1950s and 1960s, consumer product injuries and toxic exposures were on the rise, capturing the attention of both the public and policymakers. Social forces played a key role: a nascent consumer rights movement – led by advocates like Ralph Nader – pushed for accountability in industries ranging from automobiles to household goods. At the same time, high-profile accidents and research studies highlighted previously unrecognized dangers. In this atmosphere, Congress began targeting specific hazards with new laws, often enforced by whatever agency existed at the time (typically the FDA or the Department of Commerce) until a dedicated consumer safety agency would be created in the 1970s. Several important statutes from this period laid the groundwork for modern product safety compliance:

By the end of the 1960s, the need for a more coordinated approach to consumer product safety was evident. Responsibility for various product hazards was fragmented across agencies – FDA handled foods, drugs, cosmetics, and some chemicals; the Department of Commerce handled flammable fabrics and refrigerators (to prevent children getting trapped inside); the Bureau of Mines looked at fireworks and explosives; the Federal Aviation Administration even oversaw toy rockets. This piecemeal system wasn’t keeping pace with the millions of injuries occurring each year from everyday products. In 1967, President Johnson appointed the National Commission on Product Safety to study the issue. By 1970, that Commission’s report to Congress painted a bleak picture: an estimated 20–30 million consumer product-related injuries and 30,000 deaths occurred annually, and existing laws were insufficient to stem the tide. This report, combined with rising consumer activism (and media coverage of dangerous products), set the stage for a major regulatory leap.

The early 1970s marked a turning point in U.S. regulatory history. It was a decade of profound change, as the federal government created sweeping new agencies to address both environmental pollution and consumer product hazards. Several forces converged to drive this change. Socially, the public had become far more aware and concerned about health, safety, and the environment – thanks to events like the first Earth Day (1970) and influential books (e.g. Silent Spring in 1962, exposing pesticide dangers). Environmentally, the country was reeling from visible crises – rivers catching fire from chemical waste, city skies choked with smog, neighborhoods built on toxic dumps. Economically, the postwar boom’s by-products (mass consumption and industrial waste) were now recognized as threats requiring government intervention. Politically, leaders of both parties came to support stronger federal roles in protecting consumers and natural resources. In this context, the U.S. government undertook a massive regulatory expansion from 1970 onward, birthing agencies and laws that still define compliance today. Creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (1970): By the late 1960s, Americans had “awakened to the seriousness of [the] environmental pollution problem,” and there was a broad grassroots movement to “do something” about deteriorating air, water, and land. President Richard Nixon responded by proposing a new independent agency to consolidate anti-pollution programs scattered across the government.

On December 2, 1970, the EPA opened its doors, integrating pieces of various departments (e.g. air and water quality bureaus from Health, Education & Welfare; pesticide programs from Agriculture; solid waste and drinking water programs, etc.). This consolidation recognized that environmental hazards transcend state lines and industries, requiring a strong centralized enforcer. EPA’s mission was, and is, to “protect human health and the environment” by setting standards, issuing permits, and taking enforcement action against polluters. Early on, EPA enforced new laws like the Clean Air Act (1970) and Clean Water Act (1972) to crack down on the smog, sewage, and toxic discharges that had gone unchecked. The agency quickly became known for aggressive action – in its first year, EPA Administrator William Ruckelshaus even threatened cities with federal lawsuits if they didn’t stop dumping sewage into rivers

. Why did EPA get involved in product compliance? Many consumer products directly impact the environment or contain chemicals that can pollute. For example, EPA took over regulation of pesticides and set limits on pesticide residues in foods (tasks previously done by FDA). EPA also soon oversaw vehicle emissions (affecting car manufacturers) and later, things like ozone-depleting chemicals in aerosols. The creation of EPA reflected a new enforcement dynamic: federal authorities would actively police industry practices before environmental damage became irreversible, and companies across all sectors had to meet nationwide standards. Consumer Product Safety Commission (1972): On the consumer protection front, Congress established the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission in October 1972 as an independent regulatory agency. President Nixon signed the Consumer Product Safety Act (CPSA) into law, giving the CPSC a clear mandate to “protect the public against unreasonable risks of injuries and deaths associated with consumer products.”

This was a landmark in shifting enforcement to be proactive and centralized: rather than chasing hazards via separate laws and agencies, one Commission would have broad authority over thousands of products – from toys and power tools to appliances and electronics. The CPSC opened in 1973 and took over several programs pioneered by FDA and others: it assumed responsibility for enforcing the Flammable Fabrics Act, the Hazardous Substances Act (and its 1966 Child Protection amendments), the Poison Packaging Act, and even a Bureau of Standards program on household appliance safety. In effect, responsibilities previously handled by multiple organizations were consolidated within CPSC. This reorganization was driven by the realization that a dedicated body, equipped with injury data and rulemaking power, could address the “numerous issues contributing to injuries and fatalities related to consumer products” more efficiently. The rise of consumer activism (notably Ralph Nader’s campaigns on automobile and product safety) was a key factor that prompted Congress to act. As a compliance professional, it’s important to understand that CPSC from the outset had an enforcement toolkit that included setting mandatory safety standards, banning particularly hazardous products, ordering recalls or repairs of defective products, and educating the public

Under the CPSA, it became unlawful to manufacture or sell products that didn’t comply with CPSC standards or that were found to be dangerous (a profound shift from earlier eras when selling a risky product might have no immediate legal consequence). The CPSC’s creation also signaled that retailers and distributors would be held accountable, not just manufacturers – since CPSC could target anyone in the supply chain to remove a hazard. Indeed, the law explicitly made it illegal for any person to sell a consumer product that is recalled or that violates a safety standard. Enforcement was now truly end-to-end: from design and production (ensuring standards and testing) to the sales floor (monitoring and recalls). During this same period, major health and environmental laws added new layers of compliance for consumer product manufacturers:

In summary, the 1970s created the modern framework of U.S. compliance enforcement. Federal agencies were now deeply involved in proactive monitoring and rulemaking: EPA tackled environmental risks of products (chemicals, emissions, waste), CPSC oversaw the design safety and labeling of consumer goods, FDA continued safeguarding food, drugs, and cosmetics, and DOT regulated the shipment of hazardous products. Enforcement dynamics also shifted toward prevention and accountability: for example, CPSC could demand a recall before more injuries occurred, and EPA could ban a chemical before more damage was done, rather than waiting for courts and lawsuits after the fact. These changes were driven by the era’s social demand for corporate responsibility and “the right to safety” (as President Kennedy had termed in a 1962 Consumer Bill of Rights). Companies in retail and manufacturing had to build compliance programs to meet a web of regulations that were far more extensive than anything in the early 1900s.

After the regulatory revolution of the 1970s, the following two decades saw refinement and expansion of those rules – as well as new challenges from globalization. By the 1980s, consumer products were increasingly being imported from overseas suppliers, and supply chains stretched around the world. Enforcement had to adapt to monitor products at the ports and ensure foreign manufacturers complied with U.S. standards. The CPSC, for instance, established networks of import inspectors to screen shipments for safety violations, recognizing that a huge share of toys, electronics, and apparel now came from abroad. The agency also engaged with international regulators to share data and improve safety worldwide.

One practical outcome was more alignment of standards – for example, toy safety standards and electrical appliance standards started to converge across major markets, making it easier for companies to design compliant products globally. State-Level Leadership: During the 1980s, some U.S. states grew more active in consumer and environmental regulation, often pushing beyond federal requirements. This was partly because gaps in federal law left certain risks unaddressed (e.g., the original TSCA’s weakness on chemical bans), and partly due to local public pressures.

A hallmark example is California’s Proposition 65 (1986) – officially the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act. Prop 65 arose from public concern over toxic chemicals in the environment and products. It requires businesses to provide clear warnings if their products (or premises) expose consumers to chemicals known to California to cause cancer or reproductive harm. Each year the state publishes a list of such chemicals (now numbering around 900). In practice, Prop 65 led to the ubiquitous warning labels seen in California (and on many products nationwide, since companies often label all U.S. products to comply): “⚠️ WARNING: This product contains chemicals known to the State of California to cause cancer [etc].” While the law’s direct aim was to protect California’s drinking water and inform consumers, it effectively pressured manufacturers to reduce or eliminate hazardous substances to avoid having to slap scary warnings on their products. Prop 65 is enforced through civil lawsuits (including by private enforcers), which incentivized retailers and suppliers to ensure products meet the thresholds or carry warnings. The impact for compliance professionals was significant – chemical content disclosure and testing became a regular part of product compliance after Prop 65, foreshadowing today’s emphasis on transparency. California was not alone; other states like Washington and Maine passed their own chemical regulations (targeting lead, mercury, flame retardants, etc.), and many states adopted toy safety or electronics recycling laws. This “patchwork” of state rules often filled gaps left by federal law, but it also made compliance more complex for nationwide retailers. It ultimately provided impetus for federal updates (for example, the pressure of different state chemical rules helped motivate Congress to modernize TSCA in 2016).

UN Globally Harmonized Systems and International Codes: On the international stage, the late 20th century saw increased harmonization of safety standards. We discussed earlier the UN dangerous goods transport scheme; by the 1990s, efforts were underway to also harmonize chemical hazard communication (leading to the Globally Harmonized System for hazard labels and Safety Data Sheets in the 2000s). Additionally, organizations like the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) issued product safety and quality standards that many U.S. companies voluntarily followed. The UN transport classifications continued to evolve – revisions to the UN Model Regulations were issued every two years, and modes of transport (air, sea, road) each had codes (e.g. ICAO Technical Instructions for air, IMDG Code for sea) based on the UN system. This meant a U.S. supplier shipping lithium batteries abroad had to meet largely the same requirements as one shipping within the U.S., simplifying compliance in global trade.

Enforcement Shifts: In terms of enforcement dynamics, the 1980s and 90s saw regulators increasingly relying on a mix of tools: not just recalls and bans, but also standards development and industry cooperation. The CPSC, for example, worked more with voluntary standards bodies (like ANSI and ASTM) to develop consensus safety standards – sometimes making them mandatory. It also introduced a Fast Track recall program to streamline corrective actions when firms cooperated. Meanwhile, the EPA took on new environmental challenges affecting products: the 1980s brought the formal ban on leaded gasoline and lead-based paint (lead in paint was banned in 1978 by CPSC, due to its toxicity to children), the phase-out of ozone-depleting CFCs in refrigerants (under the 1987 Montreal Protocol), and new requirements for fuel efficiency in appliances (DOE’s energy conservation standards). Each of these had compliance implications for product makers – e.g., reformulating paints, redesigning aerosols and refrigerators, etc. By the end of the 1990s, compliance professionals in retail and manufacturing were dealing with multi-layered obligations: ensuring products were mechanically and electrically safe (CPSC and OSHA standards), contained no banned substances (CPSC, EPA, FDA rules), met labeling and packaging rules (CPSC, FDA, FTC, Prop 65), and that any hazardous aspects of the product’s use or disposal were properly managed (EPA, DOT, state laws). Enforcement could come from many directions – a CPSC inspector might sample toys on a store shelf for lead content; a state attorney general might sue over lack of a Prop 65 warning; an EPA regional office might fine a company for improper disposal of fluorescent lamps (hazardous waste); or DOT might penalize a distributor for not marking a chemical shipment. Retailers also increasingly imposed their own compliance requirements upstream on suppliers, conducting audits and requiring test reports, since selling non-compliant goods could result in legal liability and reputational damage. This era cemented the idea that compliance is a shared responsibility across the supply chain.

The new millennium has introduced both opportunities and challenges for product regulation and compliance. Global e-commerce has made the marketplace more accessible – and more difficult to police – than ever. A small manufacturer overseas can now sell directly to U.S. consumers via online platforms, potentially bypassing some traditional checkpoints for safety. Regulators have been adapting enforcement strategies accordingly, and new trends are shaping the future of compliance. Modern Enforcement and the Rise of E-Commerce: In the 2000s, a wave of high-profile product safety failures tested the system. In 2007, for instance, a series of toy recalls (many due to lead paint on imported toys) made headlines and alarmed parents. This spurred the U.S. Congress to pass the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act (CPSIA) of 2008, the most significant update to CPSC authority since the 1970s. CPSIA imposed tougher requirements on children’s products: lower lead and phthalate content limits, mandatory third-party safety testing and certification for kids’ goods, and a public database for consumers to report product hazards. It significantly raised the stakes for manufacturers and retailers of toys, childcare articles, and children’s apparel – non-compliance could now result in hefty penalties, and ignorance was no excuse. As one former CPSC official noted, the swift passing of CPSIA “in an expedited manner” showed how CPSC can quickly respond to emerging risks and shape proactive safety strategies.

CPSIA also explicitly extended certain obligations to importers and retailers, not just manufacturers, reflecting the reality that many U.S. brands source products from abroad and that sellers must ensure their supply chain is compliant. The e-commerce boom of the 2010s has challenged traditional regulatory approaches. Products sold through online marketplaces might come from countless independent vendors, including some outside U.S. jurisdiction. Ensuring these products meet U.S. safety standards (for electrical safety, labeling, chemicals, etc.) is a growing concern. In recent years, CPSC and Customs have ramped up surveillance at ports and online – using data analysis to flag high-risk shipments and even browsing platforms for illegal items (like banned small high-powered magnets or non-compliant cribs). New legislation, such as the STOP Act and the INFORM Consumers Act, has aimed to close gaps by requiring more transparency from e-commerce sellers and giving agencies more tools to intercept unsafe imports. The enforcement dynamic has shifted to be more data-driven and collaborative: agencies share information (domestically and internationally) about dangerous products, and there’s increasing reliance on standards (like ISO or IEC standards for electronics) that manufacturers worldwide adhere to in order to access markets. Contemporary Environmental and Social Drivers: Today’s compliance environment is heavily influenced by sustainability and social responsibility expectations. Regulators and consumers alike are pushing for products that are not only safe in use but also sustainably produced and disposed. Some emerging trends and likely future shifts include:

One constant through all these changes is the reason behind regulation: fundamentally, they arise to respond to harm or risk that the market alone has failed to control. As new products and technologies emerge (think of 3D-printed toys, autonomous drones, or AI-powered gadgets), new regulations will likely follow when novel hazards appear. Compliance professionals will need to stay agile and informed, continuing the historical trajectory of anticipating regulatory expectations rather than just reacting.

Conclusion: From the era of adulterated foods and snake-oil tonics to today’s world of smart gadgets and global supply chains, U.S. consumer product regulation has continually expanded to protect people and the planet. The involvement of federal and state agencies in enforcement grew as our understanding of risk grew – whether that risk was misbranded medicine, flammable fabric, toxic waste, or an unsafe toy. Modern compliance professionals stand on this history, using the lessons learned (often the hard way) to ensure that the products on our shelves are safer than those of yesterday. By appreciating the why behind the rules – the social outcries, environmental crises, and economic shifts that demanded action – we can better navigate and even anticipate the compliance challenges of tomorrow. As the U.S. regulatory system moves forward, shaped by new technologies and societal priorities, one thing remains constant: the commitment to safeguarding consumers, workers, and our environment from harm – a commitment built through more than a century of hard-earned progress in regulation and enforcement.

Sources:

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Milestones in U.S. Food and Drug Law.

DEA Museum. Artifact Spotlight on Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup.

U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Who We Are / What We Do.

FDA. Timeline of Consumer Safety Legislation.

U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Business Guidance on the Flammable Fabrics Act.

U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Business Guidance on the Federal Hazardous Substances Act.

Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Hazardous Materials Transportation: Historical Overview.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. EPA History: Why EPA Was Established.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA): History and Purpose.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. TSCA Implementation: Timeline and Regulatory Milestones.

Consumer Healthcare Products Association. Overview of California Proposition 65.

Product Safety Letter. Marc Schoem. Reflections on the Evolution of the U.S. CPSC and Import Safety.

U.S. Department of Transportation. Hazardous Materials Regulations Overview.

U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Public Statements on CPSIA and Risk-Based Enforcement.